My Son Ran Away To Find The Grandfather I Told Him Was A Dangerous Biker…

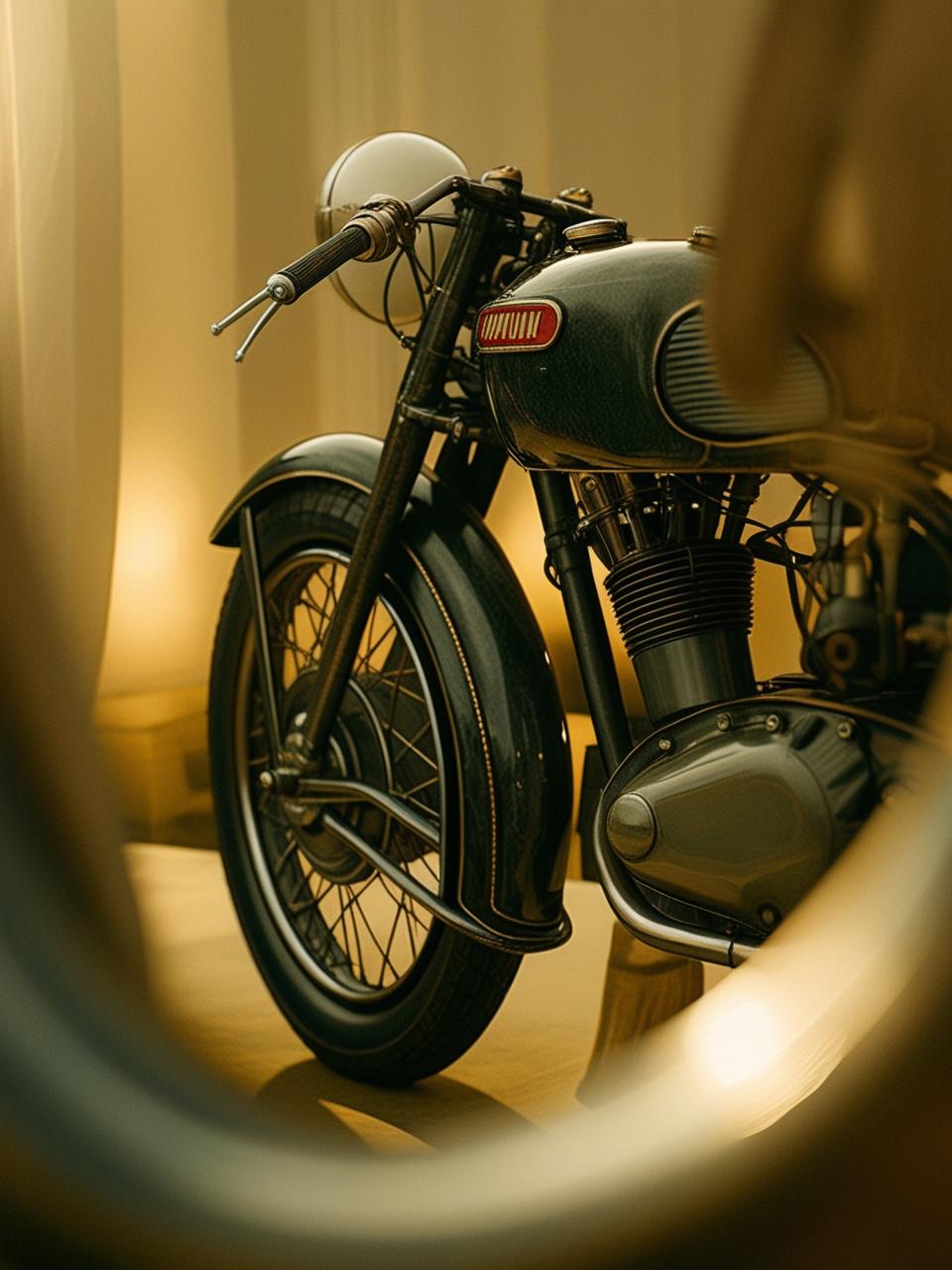

I hated my father-in-law’s motorcycle more than anything in the world because it stole my husband from me. The day that old Harley crushed John beneath its weight was the day I swore I’d never forgive Frank for introducing his son to those death machines.

We haven’t spoken since the funeral six years ago, where he had the audacity to show up with thirty leather-clad strangers who called themselves “brothers,” their motorcycles desecrating the cemetery’s peace.

I’ve spent years making sure my son Tommy never knew the truth about his grandfather. I told him his grandfather was a hard-drinking, bar-fighting former member of the Iron Horsemen Motorcycle Club with a criminal record longer than my grocery list.

But today, as I stare at my twelve-year-old son’s empty bed and the note he left behind—”Gone to find Grandpa Frank”—I realize I may have made a terrible mistake.

Because now my child is somewhere on the road, searching for a man he’s never met, a dangerous man who lives in a world I’ve spent years hiding from my son. A world of open highways, bad decisions, and men who think the rules don’t apply to them.

The police won’t do anything—”He’s not missing yet, ma’am”—and my friends don’t understand. “Just call his grandfather,” they say, as if I have Frank’s number saved in my phone, as if we exchange Christmas cards and birthday wishes. As if I haven’t spent six years pretending he doesn’t exist.

Now I’m sitting in my car outside Frank’s run-down motorcycle shop on the edge of town, the place I swore I’d never set foot in again. My hands won’t stop shaking.

Because I know once I walk through that door, I’ll have to face not just Frank, but everything I’ve been running from since they lowered my husband into the ground. And I’m terrified of what I’ll find on the other side.

I never wanted to marry into a family with motorcycles in their blood. When I met John in college, he seemed different from his father—refined, educated, with ambitions beyond the greasy motorcycle shop where Frank had spent his life.

John was studying to be an architect, wore button-down shirts, and drove a sensible sedan. The only hint of his upbringing was a small tattoo on his shoulder—a pair of wings with his father’s initials underneath.

“My dad taught me to ride when I was twelve,” he told me on our third date. “It was our thing.”

“But you don’t ride anymore?” I asked, relief evident in my voice.

His expression had darkened. “Not since college. Dad and I… we have different ideas about life.”

I took that as reassurance. John had chosen a different path. When he proposed a year later, I envisioned our future without the roar of engines or the smell of motor oil. A nice house in the suburbs, 2.5 kids, family vacations to Disney World. Normal.

Then came the wedding, and my first real encounter with Frank Sullivan. He arrived alone on his Harley, wearing what he clearly considered his “formal attire”—clean jeans, a button-up shirt under a leather vest covered in patches and pins. His gray beard was neatly trimmed, but nothing could hide the hardness in his eyes or the way he surveyed the country club venue as if expecting an ambush.

My parents were horrified. My father, a successful surgeon, could barely conceal his disdain when shaking Frank’s hand. My mother whispered not-so-quietly about “that man” throughout the reception.

Frank gave a toast that made half the room uncomfortable. “To my son,” he’d said, raising his glass. “Who found something I never could—a life beyond the road. And to Sarah,” he nodded to me, “who I hope will understand that the Sullivan men may leave the road for a while, but the road never really leaves us.”

I should have paid more attention to those words.

Three years into our marriage, with baby Tommy just learning to crawl, John came home with a familiar look in his eye—one I’d seen when he talked about his father’s old stories.

“Dad’s selling the ’89 Softail,” he announced over dinner. “The one we restored together when I was in high school.”

I focused on feeding Tommy, pretending I didn’t hear the longing in his voice.

“I was thinking about buying it,” he continued. “Just to keep it in the family. Maybe fix it up a little.”

“We don’t have room for a motorcycle,” I replied automatically. “And you haven’t ridden in years.”

“It’s like riding a bike,” he joked. “You don’t forget.”

“It’s not funny, John. Those things are dangerous. You’re a father now.”

His face hardened in a way that reminded me, suddenly and uncomfortably, of Frank. “It’s part of who I am, Sarah. You knew that when you married me.”

“I married a man who had outgrown his father’s influence,” I snapped.

We argued for weeks. I used every weapon in my arsenal—Tommy’s safety, our finances, the impracticality. In the end, I lost. The motorcycle appeared in our garage, and John disappeared into it every weekend, coming home smelling of exhaust and freedom.

Frank started visiting. They’d work on the bike together, their laughter floating through the open garage door while I sat inside, seething, feeling like an outsider in my own home. Sometimes they’d take off for hours, returning with wind-burned faces and a closeness I couldn’t penetrate.

“He’s not the man you think he is,” John told me one night after a particularly frosty dinner where I’d barely acknowledged his father. “Dad’s done some hard living, but he’s loyal to his core. Would give his last breath for family.”

“He’s a bad influence,” I countered. “You were done with that life.”

John shook his head. “I was never ‘done’ with it, Sarah. I just put it aside for a while. There’s a difference.”

The accident happened three months later. A rainy Sunday. John had promised to help me paint the nursery for the baby we’d just learned was coming. Instead, he got a call from Frank about some motorcycle rally one town over.

“Just for an hour,” he promised, kissing me goodbye. “I’ll be back before lunch.”

The policeman who came to the door said John had taken a curve too fast on the wet road. The bike slid, then flipped, pinning him underneath. He died instantly.

At the funeral, Frank stood on the opposite side of the grave, his weathered face a mask of grief I couldn’t bring myself to acknowledge. His motorcycle friends formed a semi-circle behind him, a wall of leather and denim that seemed to separate us even in our shared loss.

Later, at the house filled with casseroles and whispered condolences, Frank approached me, a small wooden box in his hands.

“John would want Tommy to have this someday,” he said hoarsely.

I didn’t take it. Didn’t even look at it. “Your motorcycle killed my husband,” I said, voice shaking with rage. “I don’t want anything from you. I don’t want Tommy to even know you exist.”

Pain flashed across his face. “Sarah, he was my son.”

“And now he’s gone. Because of you. Because of that… that death machine you put in his head.” I was crying now, months of grief and anger pouring out. “Stay away from us, Frank. I mean it.”

He stood there for a long moment, the box still extended, then slowly withdrew it and walked out the door. The sound of his motorcycle starting up in my driveway felt like a final insult.

I kept my word. I moved us to a different neighborhood, changed my phone number, and built a life where motorcycles didn’t exist. When Tommy asked about his father, I showed him pictures of John in college, at our wedding, holding him as a baby. I told him his father had been an architect who died in an accident. Not a lie, just… an edited truth.

As for Frank, I erased him completely. When Tommy asked about his grandparents, I spoke only of my parents. The Sullivan side of the family simply disappeared from our narrative.

For six years, this strategy worked. Tommy grew into a bright, curious boy who loved building things, just like his father. Sometimes I’d catch glimpses of John in the way he furrowed his brow when concentrating, or his unexpected bursts of laughter.

I told myself I was protecting him. That he was better off not knowing about Frank, about the motorcycle culture that had stolen his father.

Then came the school genealogy project.

“Mom, I need to map my family tree,” Tommy announced one evening. “Both sides.”

My stomach dropped. “Well, you know about Grandma and Grandpa Miller. And I’ve told you about Dad.”

“But what about Dad’s parents? I don’t even know their names.”

I should have been prepared for this moment. Should have had a better answer than the vague explanations I’d offered before.

“Your father wasn’t close with his family,” I said carefully. “They… had different values.”

Tommy’s eyes—so like John’s—studied me with unexpected perception. “Are they still alive? Do I have another grandpa or grandma somewhere?”

I hesitated too long.

“You’re hiding something,” he said, with the directness of a twelve-year-old. “I can tell.”

That night, I heard him on the computer after I’d gone to bed. I should have checked what he was doing, but I was tired, and Tommy had always been trustworthy.

I didn’t know he was searching social media, looking for Sullivans in our area. Didn’t know he’d found Frank’s motorcycle shop’s page, with its photos of classic bikes and grizzled men in leather.

I didn’t know until I found the note on his bed three days later.

“Gone to find Grandpa Frank. Don’t worry. Be back soon.”

Now, sitting in my car outside Sullivan’s Custom Cycles, I’m facing the consequences of six years of silence. The shop looks exactly as I remember—a converted gas station with a hand-painted sign, motorcycles lined up outside like sentinels. My hands won’t stop shaking as I reach for the door handle.

The bell jingles as I enter, and the sound brings back a flood of unwanted memories—the few times I’d come here with John in the early days, how he’d light up among the motorcycles and parts, speaking a language I couldn’t understand with his father.

The shop smells of oil, metal, and leather. A radio plays classic rock in the background. For a moment, I think it’s empty, then I notice an older man bent over a workbench in the back, his gray hair pulled into a ponytail.

“Be with you in a minute,” he calls without looking up.

My throat is dry. “Frank.”

He stiffens at my voice, slowly straightens, then turns to face me. Six years have aged him more than I expected. His face is more lined, his beard now completely gray. But his eyes are the same—intense blue, just like John’s, just like Tommy’s.

For a long moment, we just stare at each other across the expanse of the shop floor, years of unspoken accusations and grief hanging in the air between us.

“Sarah,” he finally says, neither a question nor a greeting. Just an acknowledgment.

“Is he here?” I ask, my voice higher than I intend. “Tommy. Is he here?”

Frank’s expression shifts from wariness to confusion. “Tommy? Why would he be here?”

My legs suddenly feel weak. I grab the counter for support. “He left a note. Said he was coming to find you.”

Alarm replaces confusion on Frank’s weathered face. “When?”

“This morning, I think. I was at work. When I came home for lunch, he was gone.”

Frank wipes his hands on a shop rag, his movements deliberate, but I can see tension in the set of his shoulders. “He’s never been here before?”

“No. I told you at the funeral. I didn’t want—” My voice breaks.

“You didn’t want him to know me,” Frank finishes, a hardness entering his tone. “To know his grandfather. To know anything about his father’s life.”

“His father died because of a motorcycle,” I snap, old anger surfacing. “Because you put that love of death traps in his head.”

Frank’s eyes flash. “John died because of a wet road and bad luck. Not because he rode. Not because of me.”

We might have continued this old argument, reopened wounds that had never really healed, but the urgency of Tommy’s disappearance pushes us back to the present crisis.

“How would he even know how to find you?” Frank asks.

“School project. Family tree. He must have looked you up online.”

Frank nods slowly. “The shop has a website. Social media too, though I don’t manage it myself.”

“You think he saw it and just… what? Walked here? Took a bus?”

“How far is it from your place?”

“Five miles, maybe six.”

Frank considers this. “Walkable for a determined kid. Or bikeable.” He hesitates. “What does he look like now? I haven’t seen him since…”

“Since the funeral,” I finish. The unspoken accusation hangs between us—that I’ve kept them apart, that Frank has missed six years of his grandson’s life.

I pull out my phone, find a recent picture of Tommy at his school science fair. Frank takes the phone carefully, as if it might break in his work-hardened hands. Something softens in his face as he looks at the image.

“He looks like John at that age,” he says quietly. “Same eyes.”

For a moment, we’re united in our shared connection to the man we both lost, the boy who carries his legacy.

Frank hands back my phone. “Let me make some calls. If he’s looking for me, someone might have seen him.”

I nod, watching as Frank pulls out an ancient flip phone, making a series of brief calls. Each time, he identifies himself simply as “Sullivan” and asks if anyone has seen a boy matching Tommy’s description. The curt, efficient way he handles the conversations reminds me of how John would sometimes operate in crisis—a direct, no-nonsense approach I’d always attributed to his architectural training, but now recognize might have come from his father.

After the fifth call, Frank’s expression changes. “Got something. Kid matching Tommy’s description was at Mack’s Diner about two hours ago. Asked the waitress for directions to my shop.”

My heart jumps. “That’s only a few blocks from here.”

“Mack says the boy headed this way, but obviously never made it.” Frank grabs a leather jacket from a hook by the door. “I’m going to look for him. You should wait here in case he shows up.”

I shake my head. “I’m coming with you.”

Frank gives me a measuring look, then nods once. “Fine. But we’ll cover more ground on the bike.”

I freeze. “No. Absolutely not. We’ll take my car.”

“Your car can’t get down the trails behind the shop. If he got lost or took a shortcut through the woods…” Frank doesn’t finish the sentence.

The thought of getting on a motorcycle—especially with Frank—makes my stomach clench. But the image of Tommy lost, possibly hurt, pushes through my fear.